Choosing Your Family Photographer in Carmel, Indiana: Precious Memories: A Guide to Professional Photography in Carmel, Indiana - From the first cries of a newborn to the beaming smiles of high school seniors, the fleeting moments of childhood and family create memories to cherish for a lifetime. For the best professional photographer nearby get ahold of L. Severson Photography. . That's the unquantifiable power of custom family photography sessions in Carmel and central Indiana. lenses Post-processing expertise represents another significant advantage professional photographers bring to their work. blog

Emotional Connection – Do the photographer's images convey authentic joy and meaning.

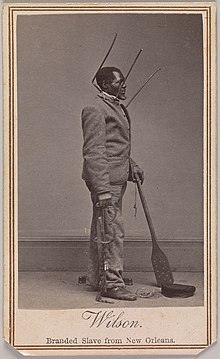

Photography is the art, application, and practice of creating images by recording light, either electronically by means of an image sensor, or chemically by means of a light-sensitive material such as photographic film. It is employed in many fields of science, manufacturing (e.g., photolithography), and business, as well as its more direct uses for art, film and video production, recreational purposes, hobby, and mass communication.[1] A person who captures or takes photographs is called a photographer.

Typically, a lens is used to focus the light reflected or emitted from objects into a real image on the light-sensitive surface inside a camera during a timed exposure. With an electronic image sensor, this produces an electrical charge at each pixel, which is electronically processed and stored in a digital image file for subsequent display or processing. The result with photographic emulsion is an invisible latent image, which is later chemically "developed" into a visible image, either negative or positive, depending on the purpose of the photographic material and the method of processing. A negative image on film is traditionally used to photographically create a positive image on a paper base, known as a print, either by using an enlarger or by contact printing.

Before the emergence of digital photography, photographs on film had to be developed to produce negatives or projectable slides, and negatives had to be printed as positive images, usually in enlarged form. This was usually done by photographic laboratories, but many amateurs did their own processing.

The word "photography" was created from the Greek roots φωτός (phōtós), genitive of φῶς (phōs), "light"[2] and γραφή (graphé) "representation by means of lines" or "drawing",[3] together meaning "drawing with light".[4]

Several people may have coined the same new term from these roots independently. Hércules Florence, a French painter and inventor living in Campinas, Brazil, used the French form of the word, photographie, in private notes which a Brazilian historian believes were written in 1834.[5] This claim is widely reported but is not yet largely recognized internationally. The first use of the word by Florence became widely known after the research of Boris Kossoy in 1980.[6]

On 25 February 1839, the German newspaper Vossische Zeitung published an article titled Photographie, discussing several priority claims, especially that of Henry Fox Talbot's, in relation to Daguerre's claim of invention.[7] The article is the earliest known occurrence of the word in public print.[8] It was signed "J.M.", believed to have been Berlin astronomer Johann von Maedler.[9] The astronomer John Herschel is also credited with coining the word, independent of Talbot, in 1839.[10]

The inventors Nicéphore Niépce, Talbot, and Louis Daguerre seem not to have known or used the word "photography", but referred to their processes as "Heliography" (Niépce), "Photogenic Drawing"/"Talbotype"/"Calotype" (Talbot), and "Daguerreotype" (Daguerre).[9]

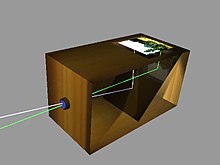

Photography is the result of combining several technical discoveries, relating to seeing an image and capturing the image. The discovery of the camera obscura ("dark chamber" in Latin) that provides an image of a scene dates back to ancient China. Greek mathematicians Aristotle and Euclid independently described a camera obscura in the 5th and 4th centuries BCE.[11][12] In the 6th century CE, Byzantine mathematician Anthemius of Tralles used a type of camera obscura in his experiments.[13]

The Arab physicist Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) (965–1040) also invented a camera obscura as well as the first true pinhole camera.[12][14][15] The invention of the camera has been traced back to the work of Ibn al-Haytham.[16] While the effects of a single light passing through a pinhole had been described earlier,[16] Ibn al-Haytham gave the first correct analysis of the camera obscura,[17] including the first geometrical and quantitative descriptions of the phenomenon,[18] and was the first to use a screen in a dark room so that an image from one side of a hole in the surface could be projected onto a screen on the other side.[19] He also first understood the relationship between the focal point and the pinhole,[20] and performed early experiments with afterimages, laying the foundations for the invention of photography in the 19th century.[15]

Leonardo da Vinci mentions natural camerae obscurae that are formed by dark caves on the edge of a sunlit valley. A hole in the cave wall will act as a pinhole camera and project a laterally reversed, upside down image on a piece of paper. Renaissance painters used the camera obscura which, in fact, gives the optical rendering in color that dominates Western Art. It is a box with a small hole in one side, which allows specific light rays to enter, projecting an inverted image onto a viewing screen or paper.

The birth of photography was then concerned with inventing means to capture and keep the image produced by the camera obscura. Albertus Magnus (1193–1280) discovered silver nitrate,[21] and Georg Fabricius (1516–1571) discovered silver chloride,[22] and the techniques described in Ibn al-Haytham's Book of Optics are capable of producing primitive photographs using medieval materials.[citation needed]

Daniele Barbaro described a diaphragm in 1566.[23] Wilhelm Homberg described how light darkened some chemicals (photochemical effect) in 1694.[24] Around 1717, Johann Heinrich Schulze used a light-sensitive slurry to capture images of cut-out letters on a bottle and on that basis many German sources and some international ones credit Schulze as the inventor of photography.[25][26] The fiction book Giphantie, published in 1760, by French author Tiphaigne de la Roche, described what can be interpreted as photography.[23]

In June 1802, British inventor Thomas Wedgwood made the first known attempt to capture the image in a camera obscura by means of a light-sensitive substance.[27] He used paper or white leather treated with silver nitrate. Although he succeeded in capturing the shadows of objects placed on the surface in direct sunlight, and even made shadow copies of paintings on glass, it was reported in 1802 that "the images formed by means of a camera obscura have been found too faint to produce, in any moderate time, an effect upon the nitrate of silver." The shadow images eventually darkened all over.[28]

The first permanent photoetching was an image produced in 1822 by the French inventor Nicéphore Niépce, but it was destroyed in a later attempt to make prints from it.[29] Niépce was successful again in 1825. In 1826 he made the View from the Window at Le Gras, the earliest surviving photograph from nature (i.e., of the image of a real-world scene, as formed in a camera obscura by a lens).[31]

Because Niépce's camera photographs required an extremely long exposure (at least eight hours and probably several days), he sought to greatly improve his bitumen process or replace it with one that was more practical. In partnership with Louis Daguerre, he worked out post-exposure processing methods that produced visually superior results and replaced the bitumen with a more light-sensitive resin, but hours of exposure in the camera were still required. With an eye to eventual commercial exploitation, the partners opted for total secrecy.

Niépce died in 1833 and Daguerre then redirected the experiments toward the light-sensitive silver halides, which Niépce had abandoned many years earlier because of his inability to make the images he captured with them light-fast and permanent. Daguerre's efforts culminated in what would later be named the daguerreotype process. The essential elements—a silver-plated surface sensitized by iodine vapor, developed by mercury vapor, and "fixed" with hot saturated salt water—were in place in 1837. The required exposure time was measured in minutes instead of hours. Daguerre took the earliest confirmed photograph of a person in 1838 while capturing a view of a Paris street: unlike the other pedestrian and horse-drawn traffic on the busy boulevard, which appears deserted, one man having his boots polished stood sufficiently still throughout the several-minutes-long exposure to be visible. The existence of Daguerre's process was publicly announced, without details, on 7 January 1839. The news created an international sensation. France soon agreed to pay Daguerre a pension in exchange for the right to present his invention to the world as the gift of France, which occurred when complete working instructions were unveiled on 19 August 1839. In that same year, American photographer Robert Cornelius is credited with taking the earliest surviving photographic self-portrait.

In Brazil, Hercules Florence had apparently started working out a silver-salt-based paper process in 1832, later naming it Photographie.

Meanwhile, a British inventor, William Fox Talbot, had succeeded in making crude but reasonably light-fast silver images on paper as early as 1834[32] but had kept his work secret. After reading about Daguerre's invention in January 1839, Talbot published his hitherto secret method in a paper to the Royal Society[32] and set about improving on it. At first, like other pre-daguerreotype processes, Talbot's paper-based photography typically required hours-long exposures in the camera, but in 1840 he created the calotype process, which used the chemical development of a latent image to greatly reduce the exposure needed and compete with the daguerreotype. In both its original and calotype forms, Talbot's process, unlike Daguerre's, created a translucent negative which could be used to print multiple positive copies; this is the basis of most modern chemical photography up to the present day, as daguerreotypes could only be replicated by rephotographing them with a camera.[33] Talbot's famous tiny paper negative of the Oriel window in Lacock Abbey, one of a number of camera photographs he made in the summer of 1835, may be the oldest camera negative in existence.[34][35]

In March 1837,[30] Steinheil, along with Franz von Kobell, used silver chloride and a cardboard camera to make pictures in negative of the Frauenkirche and other buildings in Munich, then taking another picture of the negative to get a positive, the actual black and white reproduction of a view on the object. The pictures produced were round with a diameter of 4 cm, the method was later named the "Steinheil method".

In France, Hippolyte Bayard invented his own process for producing direct positive paper prints and claimed to have invented photography earlier than Daguerre or Talbot.[36]

British chemist John Herschel made many contributions to the new field. He invented the cyanotype process, later familiar as the "blueprint". He was the first to use the terms "photography", "negative" and "positive". He had discovered in 1819 that sodium thiosulphate was a solvent of silver halides, and in 1839 he informed Talbot (and, indirectly, Daguerre) that it could be used to "fix" silver-halide-based photographs and make them completely light-fast. He made the first glass negative in late 1839.

In the March 1851 issue of The Chemist, Frederick Scott Archer published his wet plate collodion process. It became the most widely used photographic medium until the gelatin dry plate, introduced in the 1870s, eventually replaced it. There are three subsets to the collodion process; the Ambrotype (a positive image on glass), the Ferrotype or Tintype (a positive image on metal) and the glass negative, which was used to make positive prints on albumen or salted paper.

Many advances in photographic glass plates and printing were made during the rest of the 19th century. In 1891, Gabriel Lippmann introduced a process for making natural-color photographs based on the optical phenomenon of the interference of light waves. His scientifically elegant and important but ultimately impractical invention earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1908.

Glass plates were the medium for most original camera photography from the late 1850s until the general introduction of flexible plastic films during the 1890s. Although the convenience of the film greatly popularized amateur photography, early films were somewhat more expensive and of markedly lower optical quality than their glass plate equivalents, and until the late 1910s they were not available in the large formats preferred by most professional photographers, so the new medium did not immediately or completely replace the old. Because of the superior dimensional stability of glass, the use of plates for some scientific applications, such as astrophotography, continued into the 1990s, and in the niche field of laser holography, it has persisted into the 21st century.

Hurter and Driffield began pioneering work on the light sensitivity of photographic emulsions in 1876. Their work enabled the first quantitative measure of film speed to be devised.

The first flexible photographic roll film was marketed by George Eastman, founder of Kodak in 1885, but this original "film" was actually a coating on a paper base. As part of the processing, the image-bearing layer was stripped from the paper and transferred to a hardened gelatin support. The first transparent plastic roll film followed in 1889. It was made from highly flammable nitrocellulose known as nitrate film.

Although cellulose acetate or "safety film" had been introduced by Kodak in 1908,[38] at first it found only a few special applications as an alternative to the hazardous nitrate film, which had the advantages of being considerably tougher, slightly more transparent, and cheaper. The changeover was not completed for X-ray films until 1933, and although safety film was always used for 16 mm and 8 mm home movies, nitrate film remained standard for theatrical 35 mm motion pictures until it was finally discontinued in 1951.

Films remained the dominant form of photography until the early 21st century when advances in digital photography drew consumers to digital formats.[39] Although modern photography is dominated by digital users, film continues to be used by enthusiasts and professional photographers. The distinctive "look" of film based photographs compared to digital images is likely due to a combination of factors, including (1) differences in spectral and tonal sensitivity (S-shaped density-to-exposure (H&D curve) with film vs. linear response curve for digital CCD sensors),[40] (2) resolution, and (3) continuity of tone.[41]

Originally, all photography was monochrome, or black-and-white. Even after color film was readily available, black-and-white photography continued to dominate for decades, due to its lower cost, chemical stability, and its "classic" photographic look. The tones and contrast between light and dark areas define black-and-white photography.[42] Monochromatic pictures are not necessarily composed of pure blacks, whites, and intermediate shades of gray but can involve shades of one particular hue depending on the process. The cyanotype process, for example, produces an image composed of blue tones. The albumen print process, publicly revealed in 1847, produces brownish tones.

Many photographers continue to produce some monochrome images, sometimes because of the established archival permanence of well-processed silver-halide-based materials. Some full-color digital images are processed using a variety of techniques to create black-and-white results, and some manufacturers produce digital cameras that exclusively shoot monochrome. Monochrome printing or electronic display can be used to salvage certain photographs taken in color which are unsatisfactory in their original form; sometimes when presented as black-and-white or single-color-toned images they are found to be more effective. Although color photography has long predominated, monochrome images are still produced, mostly for artistic reasons. Almost all digital cameras have an option to shoot in monochrome, and almost all image editing software can combine or selectively discard RGB color channels to produce a monochrome image from one shot in color.

Color photography was explored beginning in the 1840s. Early experiments in color required extremely long exposures (hours or days for camera images) and could not "fix" the photograph to prevent the color from quickly fading when exposed to white light.

The first permanent color photograph was taken in 1861 using the three-color-separation principle first published by Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell in 1855.[43][44] The foundation of virtually all practical color processes, Maxwell's idea was to take three separate black-and-white photographs through red, green and blue filters.[43][44] This provides the photographer with the three basic channels required to recreate a color image. Transparent prints of the images could be projected through similar color filters and superimposed on the projection screen, an additive method of color reproduction. A color print on paper could be produced by superimposing carbon prints of the three images made in their complementary colors, a subtractive method of color reproduction pioneered by Louis Ducos du Hauron in the late 1860s.

Russian photographer Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii made extensive use of this color separation technique, employing a special camera which successively exposed the three color-filtered images on different parts of an oblong plate. Because his exposures were not simultaneous, unsteady subjects exhibited color "fringes" or, if rapidly moving through the scene, appeared as brightly colored ghosts in the resulting projected or printed images.

Implementation of color photography was hindered by the limited sensitivity of early photographic materials, which were mostly sensitive to blue, only slightly sensitive to green, and virtually insensitive to red. The discovery of dye sensitization by photochemist Hermann Vogel in 1873 suddenly made it possible to add sensitivity to green, yellow and even red. Improved color sensitizers and ongoing improvements in the overall sensitivity of emulsions steadily reduced the once-prohibitive long exposure times required for color, bringing it ever closer to commercial viability.

Autochrome, the first commercially successful color process, was introduced by the Lumière brothers in 1907. Autochrome plates incorporated a mosaic color filter layer made of dyed grains of potato starch, which allowed the three color components to be recorded as adjacent microscopic image fragments. After an Autochrome plate was reversal processed to produce a positive transparency, the starch grains served to illuminate each fragment with the correct color and the tiny colored points blended together in the eye, synthesizing the color of the subject by the additive method. Autochrome plates were one of several varieties of additive color screen plates and films marketed between the 1890s and the 1950s.

Kodachrome, the first modern "integral tripack" (or "monopack") color film, was introduced by Kodak in 1935. It captured the three color components in a multi-layer emulsion. One layer was sensitized to record the red-dominated part of the spectrum, another layer recorded only the green part and a third recorded only the blue. Without special film processing, the result would simply be three superimposed black-and-white images, but complementary cyan, magenta, and yellow dye images were created in those layers by adding color couplers during a complex processing procedure.

Agfa's similarly structured Agfacolor Neu was introduced in 1936. Unlike Kodachrome, the color couplers in Agfacolor Neu were incorporated into the emulsion layers during manufacture, which greatly simplified the processing. Currently, available color films still employ a multi-layer emulsion and the same principles, most closely resembling Agfa's product.

Instant color film, used in a special camera which yielded a unique finished color print only a minute or two after the exposure, was introduced by Polaroid in 1963.

Color photography may form images as positive transparencies, which can be used in a slide projector, or as color negatives intended for use in creating positive color enlargements on specially coated paper. The latter is now the most common form of film (non-digital) color photography owing to the introduction of automated photo printing equipment. After a transition period centered around 1995–2005, color film was relegated to a niche market by inexpensive multi-megapixel digital cameras. Film continues to be the preference of some photographers because of its distinctive "look".

In 1981, Sony unveiled the first consumer camera to use a charge-coupled device for imaging, eliminating the need for film: the Sony Mavica. While the Mavica saved images to disk, the images were displayed on television, and the camera was not fully digital.

The first digital camera to both record and save images in a digital format was the Fujix DS-1P created by Fujifilm in 1988.[45]

In 1991, Kodak unveiled the DCS 100, the first commercially available digital single-lens reflex camera. Although its high cost precluded uses other than photojournalism and professional photography, commercial digital photography was born.

Digital imaging uses an electronic image sensor to record the image as a set of electronic data rather than as chemical changes on film.[46] An important difference between digital and chemical photography is that chemical photography resists photo manipulation because it involves film and photographic paper, while digital imaging is a highly manipulative medium. This difference allows for a degree of image post-processing that is comparatively difficult in film-based photography and permits different communicative potentials and applications.

Digital photography dominates the 21st century. More than 99% of photographs taken around the world are through digital cameras, increasingly through smartphones.

A large variety of photographic techniques and media are used in the process of capturing images for photography. These include the camera; dualphotography; full-spectrum, ultraviolet and infrared media; light field photography; and other imaging techniques.

The camera is the image-forming device, and a photographic plate, photographic film or a silicon electronic image sensor is the capture medium. The respective recording medium can be the plate or film itself, or a digital magnetic or electronic memory.[47]

Photographers control the camera and lens to "expose" the light recording material to the required amount of light to form a "latent image" (on plate or film) or RAW file (in digital cameras) which, after appropriate processing, is converted to a usable image. Digital cameras use an electronic image sensor based on light-sensitive electronics such as charge-coupled device (CCD) or complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) technology. The resulting digital image is stored electronically, but can be reproduced on a paper.

The camera (or 'camera obscura') is a dark room or chamber from which, as far as possible, all light is excluded except the light that forms the image. It was discovered and used in the 16th century by painters. The subject being photographed, however, must be illuminated. Cameras can range from small to very large, a whole room that is kept dark while the object to be photographed is in another room where it is properly illuminated. This was common for reproduction photography of flat copy when large film negatives were used (see Process camera).

As soon as photographic materials became "fast" (sensitive) enough for taking candid or surreptitious pictures, small "detective" cameras were made, some actually disguised as a book or handbag or pocket watch (the Ticka camera) or even worn hidden behind an Ascot necktie with a tie pin that was really the lens.

The movie camera is a type of photographic camera that takes a rapid sequence of photographs on recording medium. In contrast to a still camera, which captures a single snapshot at a time, the movie camera takes a series of images, each called a "frame". This is accomplished through an intermittent mechanism. The frames are later played back in a movie projector at a specific speed, called the "frame rate" (number of frames per second). While viewing, a person's eyes and brain merge the separate pictures to create the illusion of motion.[48]

Photographs, both monochrome and color, can be captured and displayed through two side-by-side images that emulate human stereoscopic vision. Stereoscopic photography was the first that captured figures in motion.[49] While known colloquially as "3-D" photography, the more accurate term is stereoscopy. Such cameras have long been realized by using film and more recently in digital electronic methods (including cell phone cameras).

Dualphotography consists of photographing a scene from both sides of a photographic device at once (e.g. camera for back-to-back dualphotography, or two networked cameras for portal-plane dualphotography). The dualphoto apparatus can be used to simultaneously capture both the subject and the photographer, or both sides of a geographical place at once, thus adding a supplementary narrative layer to that of a single image.[50]

Ultraviolet and infrared films have been available for many decades and employed in a variety of photographic avenues since the 1960s. New technological trends in digital photography have opened a new direction in full spectrum photography, where careful filtering choices across the ultraviolet, visible and infrared lead to new artistic visions.

Modified digital cameras can detect some ultraviolet, all of the visible and much of the near infrared spectrum, as most digital imaging sensors are sensitive from about 350 nm to 1000 nm. An off-the-shelf digital camera contains an infrared hot mirror filter that blocks most of the infrared and a bit of the ultraviolet that would otherwise be detected by the sensor, narrowing the accepted range from about 400 nm to 700 nm.[51]

Replacing a hot mirror or infrared blocking filter with an infrared pass or a wide spectrally transmitting filter allows the camera to detect the wider spectrum light at greater sensitivity. Without the hot-mirror, the red, green and blue (or cyan, yellow and magenta) colored micro-filters placed over the sensor elements pass varying amounts of ultraviolet (blue window) and infrared (primarily red and somewhat lesser the green and blue micro-filters).

Uses of full spectrum photography are for fine art photography, geology, forensics and law enforcement.

Layering is a photographic composition technique that manipulates the foreground, subject or middle-ground, and background layers in a way that they all work together to tell a story through the image.[52] Layers may be incorporated by altering the focal length, distorting the perspective by positioning the camera in a certain spot.[53] People, movement, light and a variety of objects can be used in layering.[54]

Digital methods of image capture and display processing have enabled the new technology of "light field photography" (also known as synthetic aperture photography). This process allows focusing at various depths of field to be selected after the photograph has been captured.[55] As explained by Michael Faraday in 1846, the "light field" is understood as 5-dimensional, with each point in 3-D space having attributes of two more angles that define the direction of each ray passing through that point.

These additional vector attributes can be captured optically through the use of microlenses at each pixel point within the 2-dimensional image sensor. Every pixel of the final image is actually a selection from each sub-array located under each microlens, as identified by a post-image capture focus algorithm.

Besides the camera, other methods of forming images with light are available. For instance, a photocopy or xerography machine forms permanent images but uses the transfer of static electrical charges rather than photographic medium, hence the term electrophotography. Photograms are images produced by the shadows of objects cast on the photographic paper, without the use of a camera. Objects can also be placed directly on the glass of an image scanner to produce digital pictures.

Amateur photographers take photos for personal use, as a hobby or out of casual interest, rather than as a business or job. The quality of amateur work can be comparable to that of many professionals. Amateurs can fill a gap in subjects or topics that might not otherwise be photographed if they are not commercially useful or salable. Amateur photography grew during the late 19th century due to the popularization of the hand-held camera.[56] Twenty-first century social media and near-ubiquitous camera phones have made photographic and video recording pervasive in everyday life. In the mid-2010s smartphone cameras added numerous automatic assistance features like color management, autofocus face detection and image stabilization that significantly decreased skill and effort needed to take high quality images.[57]

|

|

Commercial photography is probably best defined as any photography for which the photographer is paid for images rather than works of art. In this light, money could be paid for the subject of the photograph or the photograph itself. The commercial photographic world could include:

During the 20th century, both fine art photography and documentary photography became accepted by the English-speaking art world and the gallery system. In the United States, a handful of photographers, including Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, John Szarkowski, F. Holland Day, and Edward Weston, spent their lives advocating for photography as a fine art. At first, fine art photographers tried to imitate painting styles. This movement is called Pictorialism, often using soft focus for a dreamy, 'romantic' look. In reaction to that, Weston, Ansel Adams, and others formed the Group f/64 to advocate 'straight photography', the photograph as a (sharply focused) thing in itself and not an imitation of something else.

The aesthetics of photography is a matter that continues to be discussed regularly, especially in artistic circles. Many artists argued that photography was the mechanical reproduction of an image. If photography is authentically art, then photography in the context of art would need redefinition, such as determining what component of a photograph makes it beautiful to the viewer. The controversy began with the earliest images "written with light"; Nicéphore Niépce, Louis Daguerre, and others among the very earliest photographers were met with acclaim, but some questioned if their work met the definitions and purposes of art.

Clive Bell in his classic essay Art states that only "significant form" can distinguish art from what is not art.

There must be some one quality without which a work of art cannot exist; possessing which, in the least degree, no work is altogether worthless. What is this quality? What quality is shared by all objects that provoke our aesthetic emotions? What quality is common to Sta. Sophia and the windows at Chartres, Mexican sculpture, a Persian bowl, Chinese carpets, Giotto's frescoes at Padua, and the masterpieces of Poussin, Piero della Francesca, and Cezanne? Only one answer seems possible – significant form. In each, lines and colors combined in a particular way, certain forms and relations of forms, stir our aesthetic emotions.[58]

On 7 February 2007, Sotheby's London sold the 2001 photograph 99 Cent II Diptychon for an unprecedented $3,346,456 to an anonymous bidder, making it the most expensive at the time.[59]

Conceptual photography turns a concept or idea into a photograph. Even though what is depicted in the photographs are real objects, the subject is strictly abstract.

In parallel to this development, the then largely separate interface between painting and photography was closed in the second half of the 20th century with the chemigram of Pierre Cordier and the chemogram of Josef H. Neumann.[60] In 1974 the chemograms by Josef H. Neumann concluded the separation of the painterly background and the photographic layer by showing the picture elements in a symbiosis that had never existed before, as an unmistakable unique specimen, in a simultaneous painterly and at the same time real photographic perspective, using lenses, within a photographic layer, united in colors and shapes. This Neumann chemogram from the 1970s thus differs from the beginning of the previously created cameraless chemigrams of a Pierre Cordier and the photogram Man Ray or László Moholy-Nagy of the previous decades. These works of art were almost simultaneous with the invention of photography by various important artists who characterized Hippolyte Bayard, Thomas Wedgwood, William Henry Fox Talbot in their early stages, and later Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy in the twenties and by the painter in the thirties Edmund Kesting and Christian Schad by draping objects directly onto appropriately sensitized photo paper and using a light source without a camera. [61]

Photojournalism is a particular form of photography (the collecting, editing, and presenting of news material for publication or broadcast) that employs images in order to tell a news story. It is now usually understood to refer only to still images, but in some cases the term also refers to video used in broadcast journalism. Photojournalism is distinguished from other close branches of photography (e.g., documentary photography, social documentary photography, street photography or celebrity photography) by complying with a rigid ethical framework which demands that the work be both honest and impartial whilst telling the story in strictly journalistic terms. Photojournalists create pictures that contribute to the news media, and help communities connect with one other. Photojournalists must be well informed and knowledgeable about events happening right outside their door. They deliver news in a creative format that is not only informative, but also entertaining, including sports photography.

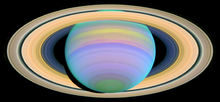

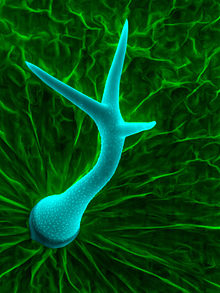

The camera has a long and distinguished history as a means of recording scientific phenomena from the first use by Daguerre and Fox-Talbot, such as astronomical events (eclipses for example), small creatures and plants when the camera was attached to the eyepiece of microscopes (in photomicroscopy) and for macro photography of larger specimens. The camera also proved useful in recording crime scenes and the scenes of accidents, such as the Wootton bridge collapse in 1861. The methods used in analysing photographs for use in legal cases are collectively known as forensic photography. Crime scene photos are usually taken from three vantage points: overview, mid-range, and close-up.[62]

In 1845 Francis Ronalds, the Honorary Director of the Kew Observatory, invented the first successful camera to make continuous recordings of meteorological and geomagnetic parameters. Different machines produced 12- or 24- hour photographic traces of the minute-by-minute variations of atmospheric pressure, temperature, humidity, atmospheric electricity, and the three components of geomagnetic forces. The cameras were supplied to numerous observatories around the world and some remained in use until well into the 20th century.[63][64] Charles Brooke a little later developed similar instruments for the Greenwich Observatory.[65]

Science regularly uses image technology that has derived from the design of the pinhole camera to avoid distortions that can be caused by lenses. X-ray machines are similar in design to pinhole cameras, with high-grade filters and laser radiation.[66] Photography has become universal in recording events and data in science and engineering, and at crime scenes or accident scenes. The method has been much extended by using other wavelengths, such as infrared photography and ultraviolet photography, as well as spectroscopy. Those methods were first used in the Victorian era and improved much further since that time.[67]

The first photographed atom was discovered in 2012 by physicists at Griffith University, Australia. They used an electric field to trap an "Ion" of the element, Ytterbium. The image was recorded on a CCD, an electronic photographic film.[68]

Wildlife photography involves capturing images of various forms of wildlife. Unlike other forms of photography such as product or food photography, successful wildlife photography requires a photographer to choose the right place and right time when specific wildlife are present and active. It often requires great patience and considerable skill and command of the right photographic equipment.[69]

There are many ongoing questions about different aspects of photography. In her On Photography (1977), Susan Sontag dismisses the objectivity of photography. This is a highly debated subject within the photographic community.[70] Sontag argues, "To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting one's self into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge, and therefore like power."[71] Photographers decide what to take a photo of, what elements to exclude and what angle to frame the photo, and these factors may reflect a particular socio-historical context. Along these lines, it can be argued that photography is a subjective form of representation.

Modern photography has raised a number of concerns on its effect on society. In Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window (1954), the camera is presented as promoting voyeurism. 'Although the camera is an observation station, the act of photographing is more than passive observing'.[71]

The camera doesn't rape or even possess, though it may presume, intrude, trespass, distort, exploit, and, at the farthest reach of metaphor, assassinate – all activities that, unlike the sexual push and shove, can be conducted from a distance, and with some detachment.[71]

Digital imaging has raised ethical concerns because of the ease of manipulating digital photographs in post-processing. Many photojournalists have declared they will not crop their pictures or are forbidden from combining elements of multiple photos to make "photomontages", passing them as "real" photographs. Today's technology has made image editing relatively simple for even the novice photographer. However, recent changes of in-camera processing allow digital fingerprinting of photos to detect tampering for purposes of forensic photography.

Photography is one of the new media forms that changes perception and changes the structure of society.[72] Further unease has been caused around cameras in regards to desensitization. Fears that disturbing or explicit images are widely accessible to children and society at large have been raised. Particularly, photos of war and pornography are causing a stir. Sontag is concerned that "to photograph is to turn people into objects that can be symbolically possessed". Desensitization discussion goes hand in hand with debates about censored images. Sontag writes of her concern that the ability to censor pictures means the photographer has the ability to construct reality.[71]

One of the practices through which photography constitutes society is tourism. Tourism and photography combine to create a "tourist gaze"[73] in which local inhabitants are positioned and defined by the camera lens. However, it has also been argued that there exists a "reverse gaze"[74] through which indigenous photographees can position the tourist photographer as a shallow consumer of images.

Photography is both restricted and protected by the law in many jurisdictions. Protection of photographs is typically achieved through the granting of copyright or moral rights to the photographer. In the United States, photography is protected as a First Amendment right and anyone is free to photograph anything seen in public spaces as long as it is in plain view.[75] In the UK, a recent law (Counter-Terrorism Act 2008) increases the power of the police to prevent people, even press photographers, from taking pictures in public places.[76] In South Africa, any person may photograph any other person, without their permission, in public spaces and the only specific restriction placed on what may not be photographed by government is related to anything classed as national security. Each country has different laws.

According to Nazir Ahmed if only Ibn-Haitham's fellow-workers and students had been as alert as he, they might even have invented the art of photography since al-Haitham's experiments with convex and concave mirrors and his invention of the "pinhole camera" whereby the inverted image of a candle-flame is projected were among his many successes in experimentation. One might likewise almost claim that he had anticipated much that the nineteenth century Fechner did in experimentation with after-images.

The invention of the camera can be traced back to the 10th century when the Arab scientist Al-Hasan Ibn al-Haytham alias Alhacen provided the first clear description and correct analysis of the (human) vision process. Although the effects of single light passing through the pinhole have already been described by the Chinese Mozi (Lat. Micius) (5th century B), the Greek Aristotle (4th century BC), and the Arab

The principles of the camera obscura first began to be correctly analysed in the eleventh century, when they were outlined by Ibn al-Haytham.

Alhazen used the camera obscura particularly for observing solar eclipses, as indeed Aristotle is said to have done, and it seems that, like Shen Kua, he had predecessors in its study, since he did not claim it as any new finding of his own. But his treatment of it was competently geometrical and quantitative for the first time.

All these scientists experimented with a small hole and light but none of them suggested that a screen is used so an image from one side of a hole in surface could be projected at the screen on the other. First one to do so was Alhazen (also known as Ibn al-Haytham) in 11th century.

The genius of Shen Kua's insight into the relation of focal point and pinhole can better be appreciated when we read in Singer that this was first understood in Europe by Leonardo da Vinci (+ 1452 to + 1519), almost five hundred years later. A diagram showing the relation occurs in the Codice Atlantico, Leonardo thought that the lens of the eye reversed the pinhole effect, so that the image did not appear inverted on the retina; though in fact it does. Actually, the analogy of focal-point and pin-point must have been understood by Ibn al-Haitham, who died just about the time when Shen Kua was born.

... But the first person to use this property to produce a photographic image was German physicist Johann Heinrich Schulze. In 1727, Schulze made a paste of silver nitrate and chalk, placed the mixture in a glass bottle, and wrapped the bottle in ...

from Helmut Gernsheim's article, "The 150th Anniversary of Photography," in History of Photography, Vol. I, No. 1, January 1977: ...In 1822, Niépce coated a glass plate... The sunlight passing through... This first permanent example... was destroyed... some years later.

|

Carmel, Indiana

|

|

|---|---|

The Palladium at the Center for the Performing Arts and Carmel City Center

|

|

| Motto:

"A Partnership for Tomorrow"

|

|

| Coordinates: 39°58′05″N 86°06′45″W / 39.96806°N 86.11250°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Indiana |

| County | Hamilton |

| Township | Clay (coterminous) |

| Government

|

|

| • Mayor | Sue Finkam (R) (2024–present)[1][2] |

| Area | |

|

• Total

|

50.17 sq mi (129.94 km2) |

| • Land | 49.09 sq mi (127.13 km2) |

| • Water | 1.08 sq mi (2.80 km2) |

| Elevation | 843 ft (257 m) |

| Population

(2020)[5]

|

|

|

• Total

|

99,757 |

|

• Estimate

(2021)

|

100,777 |

| • Density | 2,032.3/sq mi (784.7/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes |

46032, 46033, 46074, 46082, 46280, 46290[6]

|

| Area code(s) | 317, 463 |

| FIPS code | 18-10342 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2393750[4] |

| Website | www |

Carmel (/ˈkɑːrməl/) is a suburban city in Hamilton County, Indiana, United States, immediately north of Indianapolis. With a population of 99,757 as of the 2020 census, the city spans 49 square miles (130 km2) across Clay Township and is bordered by the White River to the east and the Boone County line to the west. Carmel was home to one of the first electronic automated traffic signals in the country,[7] and has now constructed 141 roundabouts between 1989 and 2022.[8][9]

In the 1820s, the government put the lands in the area on sale, leading many farmers to settle on the west bank of White River.[10] The original settlers were predominantly Quakers.[10][11]

Carmel was originally called "Bethlehem". It was platted and recorded in 1837 by Daniel Warren, Alexander Mills, John Phelps, and Seth Green,[12]: 241 who donated their adjoining properties of equal size to create the town. The donated parcels were situated along the Indianapolis-Peru Road (now Westfield Boulevard). The Carmel Clay Historical Society also started its first activities in 1837.[10]

The plot first established in Bethlehem, located at the intersection of Rangeline Road and Main Street, was marked by a clock tower donated by the local Rotary Club in 2002.[13]

A post office was established as "Carmel" in 1846 because Indiana already had a post office called Bethlehem.[14] The name Carmel is a reference to 1 Samuel 25:2 mentioning the biblical settlement Carmel.[10] The town of Bethlehem was renamed "Carmel" and incorporated in 1874.[10][12]: 247

The Monon Railroad started operations in the city in 1883. Electricity and telephone lines arrived during the first decade of the 20th century. The city's first library was started by the local Wednesday Literary Club and schoolteacher Mahlon Luther Hains in 1904. With a grant from the Carnegie Foundation, the library was built at 40 East Main Streett in 1913. During the first half of the 20th century, the city was the host on and off of the Carmel Horse Show. The town's only bank closed in 1930.[10]

In 1924, one of the first automatic traffic signals in the U.S. was installed at the intersection of Main Street and Rangeline Road. The signal was the invention of Leslie Haines and is currently in the old train station on the Monon Trail.[15]

The Carmel Monon Depot, John Kinzer House, and Thornhurst Addition are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[16][17]

During the 1950s and 1960s, the city anticipated a demographic boom and built large new public schools, leading to the creation of the Carmel Clay School District in 1964 (and the Carmel Clay Educational Foundation in 1967). Six churches were built during the 1950s. The urban expansion was so fast that a 1958 Indianapolis Star article tagged it a "bedroom community", but one that could contribute to sustain the growth of Indianapolis. Construction of Interstate 465 started in 1967 and created the proper conditions for a rapid demographic growth. A new $330,000 library was built and opened in 1971.[10]

The first Chamber of Commerce opened in 1960 but closed two years later. With the demographic boom of the 1970s, it reopened in 1970.[10]

The Carmel Symphony was launched by Latvian immigrant Viktors Ziedonis in 1976.[10]

By the end of the 20th century, Carmel was one of Indiana's fastest growing cities. Suburban districts quickly replaced agricultural lands. The last farm operating within the city limits closed in 1993.[10]

Carmel occupies the southwestern part of Hamilton County, adjacent to Indianapolis and, with the annexation of Home Place in 2018, is now entirely coextensive with Clay Township. It is bordered to the north by Westfield, to the northeast by Noblesville, to the east by Fishers, to the south by Indianapolis in Marion County, and to the west by Zionsville in Boone County. The center of Carmel is 15 miles (24 km) north of the center of Indianapolis.

According to the 2010 census, Carmel has a total area of 48.545 square miles (125.73 km2), of which 47.46 square miles (122.92 km2) (or 97.76%) is land and 1.085 square miles (2.81 km2) (or 2.24%) is water.[18]

Major east–west streets in Carmel generally end in a 6 and include 96th Street (the southern border), 106th, 116th, 126th, 131st, 136th, and 146th (which marks the northern border). The numbering system is aligned to that of Marion and Hamilton counties. Main Street (131st) runs east–west through Carmel's Art & Design District; Carmel Drive runs generally east–west through the main shopping area, and City Center Drive runs east–west near Carmel's City Center project.

North–south streets are not numbered and include (west to east) Michigan, Shelborne, Towne, Ditch, Spring Mill, Meridian, Guilford, Rangeline, Keystone, Carey, Gray, Hazel Dell, and River. Some of these roads are continuations of corresponding streets in Indianapolis. Towne Road replaces the name Township Line Road at 96th Street, while Westfield Boulevard becomes Rangeline north of 116th Street. Meridian Street (US 31) and Keystone Parkway (formerly Keystone Avenue/SR 431) are the major thoroughfares, extending from 96th Street in the south and merging just south of 146th Street. The City of Carmel is noted for having well over 100 roundabouts within its borders.[19][20]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 92 | — | |

| 1890 | 471 | 412.0% | |

| 1900 | 498 | 5.7% | |

| 1910 | 626 | 25.7% | |

| 1920 | 598 | −4.5% | |

| 1930 | 682 | 14.0% | |

| 1940 | 771 | 13.0% | |

| 1950 | 1,009 | 30.9% | |

| 1960 | 1,442 | 42.9% | |

| 1970 | 6,691 | 364.0% | |

| 1980 | 18,272 | 173.1% | |

| 1990 | 25,380 | 38.9% | |

| 2000 | 37,733 | 48.7% | |

| 2010 | 79,191 | 109.9% | |

| 2020 | 99,757 | 26.0% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 100,777 | [5] | 1.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[21] 2018 Estimate[22] |

|||

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[23] | Pop 2010[24] | Pop 2020[25] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 34,467 | 66,295 | 75,534 | 91.34% | 83.72% | 75.72% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 550 | 2,299 | 3,256 | 1.46% | 2.90% | 3.26% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 45 | 104 | 65 | 0.12% | 0.13% | 0.07% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 1,645 | 6,988 | 11,966 | 4.36% | 8.82% | 12.00% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 12 | 17 | 20 | 0.03% | 0.02% | 0.02% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 48 | 169 | 451 | 0.13% | 0.21% | 0.45% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 317 | 1,310 | 3,944 | 0.84% | 1.65% | 3.95% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 649 | 2,009 | 4,521 | 1.72% | 2.54% | 4.53% |

| Total | 37,733 | 79,191 | 99,757 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

⬤ Black

⬤ Asian

⬤ Hispanic

⬤ Multiracial

⬤ Native American/Other

According to a 2017 estimate, the median household income in the city was $109,201.

The median home price between 2013 and 2017 was $320,400.[26]

As of the census[27] of 2010, there were 79,191 people, 28,997 households, and 21,855 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,668.6 inhabitants per square mile (644.3/km2). There were 30,738 housing units at an average density of 647.7 units per square mile (250.1 units/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 85.4% White, 3.0% African American, 0.2% Native American, 8.9% Asian, 0.7% from other races, and 1.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 2.5% of the population.

There were 28,997 households, of which 41.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 66.6% were married couples living together, 6.3% had a female householder with no partner present, 2.4% had a male householder with no partner present, and 24.6% were non-families. 20.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 6.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.71 and the average family size was 3.18.

The median age in the city was 39.2 years. 29.4% of residents were under the age of 18; 5.3% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 25.2% were from 25 to 44; 29.7% were from 45 to 64; and 10.4% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.7% male and 51.3% female.

The Meridian Corridor serves as a large concentration of corporate office space within the city. It is home to more than 40 corporate headquarters and many more regional offices. Several large companies reside in Carmel, and it serves as the national headquarters for OPENLANE (formerly KAR Global), Allegion, CNO Financial Group, MISO, and Delta Faucet.

As of January 2017[update], the city's 10 largest employers were:[28]

| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | CNO Financial Group | 1,600 |

| 2 | GEICO | 1,250 |

| 3 | RCI | 1,125 |

| 4 | Capital Group Companies | 975 |

| 5 | Liberty Mutual | 900 |

| 6 | KAR Auction Services (Adesa) | 892 |

| 7 | IU Health North | 800 |

| 8 | Midcontinent ISO | 700 |

| 9 | NextGear Capital | 694 |

| 10 | Allegion | 595 |

Carmel also serves as the global headquarters of the North American Interfraternity Conference, an association of multiple fraternities and sororities. Carmel also serves as the global headquarters for seven fraternities and sororities: Alpha Kappa Lambda, Alpha Sigma Phi, Lambda Chi Alpha, Phi Kappa Sigma, Theta Chi, Sigma Delta Tau, and Sigma Kappa.[29]

Indiana's only Gran Fondo, this cycling event attracts professional cyclists as well as recreational riders. In 2019, the event is the World Championship for the Gran Fondo World Tour. Each route is fully supported with food, drinks, and mechanical support.[30]

Founded in 1998, the Carmel Farmers Market is one of the largest in the state of Indiana, with over 60 vendors of Indiana-grown and/or produced edible products. The market, which is managed by an all-volunteer committee, is held each Saturday morning from mid-May through the first weekend of October on Center Green at the Palladium, the farmers market attracts over 60,000 people a year.[31]

A $24.5 million water park and fitness center is the centerpiece of Carmel's $55 million Central Park, which opened in 2007.[citation needed] The Outdoor Water Park consists of two water slides, a drop slide, a rock-climbing wall, a lazy river, a kiddie pool, a large zero depth activity pool, Flowrider, and a lap pool. The fitness center consists of an indoor lap pool, a recreation pool with its own set of water slides and a snack bar, gymnasium, 1⁄8-mile (0.20 km) indoor running track, and the Kids Zone childcare. The building housing the Carmel Clay Parks Department offices is connected by an elevated walkway over the Monon Trail.[citation needed]

The Monon Greenway is a multi-use trail that is part of the Rails-to-Trails movement. It runs from 10th Street near downtown Indianapolis through Broad Ripple and then crosses into Carmel at 96th Street and continues north through 146th Street into Westfield and continues to Sheridan. The trail ends in Sheridan near the intersection of Opel and 236th streets. In January 2006, speed limit signs of 15 to 20 miles per hour (24 to 32 km/h) were added to sections of the trail in Hamilton County.

Designed to promote small businesses and local artisans, Carmel's Arts and Design District and City Center is in Old Town Carmel and flanked by Carmel High School on the east and the Monon Greenway on the west, with the state goal of celebrating the creativity and craftsmanship of the miniature art form.. The district includes the Carmel Clay Public Library,[32] the Hamilton County Convention & Visitor's Bureau and Welcome Center, and a collection of art galleries, boutiques, interior designers, cafes, and restaurants. Lifelike sculptures by John Seward Johnson II ornament the streets of the district.

The district hosts several annual events and festivals. The Carmel Artomobilia Collector Car Show showcases classic, vintage, exotic and rare cars, along with art inspired by automobile design.[33] Every September, the Carmel International Arts Festival features a juried art exhibit of artists from around the world,[34] concerts, dance performances, and hands-on activities for children.

In the heart of the district stands the Museum of Miniature Houses, open since 1993. The museum has seven exhibit rooms of fully furnished houses, room displays, and collections of miniature glassware, clocks, tools, and dolls.

Carmel City Center is a one-million-square-foot (93,000 m2), $300 million, mixed-use development located in the heart of Carmel.[35] Carmel City Center is home to The Palladium at the Center for the Performing Arts, which includes a 1,600-seat concert hall, 500-seat theater, and 200-seat black box theater. This pedestrian-based master plan development is located at the southwest corner of City Center Drive (126th Street) and Range Line Road. The Monon Greenway runs directly through the project. Carmel City Center was developed as a public/private partnership.

Clay Terrace is one of the largest retail centers in Carmel. Other shopping areas include Carmel City Center,[36] Mohawk Trails Plaza, and Merchants' Square. The Carmel Arts & Design District has a number of retail establishments along Main Street, Range Line Road, 3rd Avenue, and 2nd Street.[37]

Ground was broken for the Japanese Garden south of City Hall in 2007. The garden was dedicated in 2009 as the 15th anniversary of Carmel's Sister City relationship with Kawachinagano, Japan, was celebrated.[38] An Azumaya-style tea gazebo was constructed in 2011 and dedicated on May 2 of that year.[39]

The Great American Songbook Foundation is the nation's only foundation and museum dedicated to preserving the music of the early to mid-1900s. The foundation is led by Michael Feinstein, who is also the artistic director of the Center for the Performing Arts.[40][41]

Founded in 2017, under the direction of then Mayor James Brainard,[42] Carmel Christkindlmarkt is an open air Christmas market known for its Glühwein Pyramid, a 33-foot tall (10 m) structure lit with 3000 bulbs.[43] The market is one of Indiana's top tourist attractions hosting over 400,000 visitors annually.[44][45]

The government consists of a mayor and a city council. The current mayor is Sue Finkam, who has served since 2024.[46] The city council consists of nine members. Six are elected from individual districts and three are elected at-large.

In mid-2017, the city council was considering a multimillion-dollar bond issue that would cover the cost of roundabouts, paths, roadwork, land acquisition by the Carmel Redevelopment Commission and would include the purchase of an antique carousel[47] from a Canadian amusement park for an estimated purchase price of CAD $3 million, approximately US$2.25 million.[48] However, a citizen led petition drive against the purchase caused the city council to remove it from the bond issue.[49]

According to the Indiana Department of Local Government Finance, as of 2019 the City of Carmel had an overall debt load of $1.3 billion.[50]

| No. | Portrait | Mayor | Term of office[51] | Election | Party[52][53] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Albert Pickett | January 1, 1976 – January 1, 1980 |

1975 | Republican | ||

| 2 | Jane A. Reiman | January 1, 1980 – January 1, 1988 |

1979 | Republican | ||

| 1983 | ||||||

| 3 | Dorothy J. Hancock | January 1, 1988 – January 1, 1992 |

1987 | Republican | ||

| 4 | Ted Johnson | January 1, 1992 – January 1, 1996 |

1991 | Republican | ||

| 5 |  |

James Brainard | January 1, 1996 – January 1, 2024 |

1995 | Republican | |

| 1999 | ||||||

| 2003 | ||||||

| 2007 | ||||||

| 2011 | ||||||

| 2015 | ||||||

| 2019 | ||||||

| 6 | Sue Finkam[54] | January 1, 2024 – Incumbent |

2023 | Republican | ||

The Carmel Clay Schools[55] district has 11 elementary schools (Kindergarten - Grade 5), three middle schools (Grades 6–8), and one high school (Grades 9–12).[55] Student enrollment for the district is above 14,500.[56]

The elementary schools include:

The middle schools include:

All middle schools feed into Carmel High School.[71]

Carmel has several private schools, including:

Carmel has six sister cities as designated by Sister Cities International.[77]

A photographer (the Greek φῶς (phos), meaning "light", and γραφή (graphê), meaning "drawing, writing", together meaning "drawing with light")[1] is a person who uses a camera to make photographs.

As in other arts, the definitions of amateur and professional are not entirely categorical.

An amateur photographer takes snapshots for pleasure to remember events, places or friends with no intention of selling the images to others.

A professional photographer is likely to take photographs for a session and image purchase fee, by salary or through the display, resale or use of those photographs.[3]

A professional photographer may be an employee, for example of a newspaper, or may contract to cover a particular planned event such as a wedding or graduation, or to illustrate an advertisement. Others, like fine art photographers, are freelancers, first making an image and then licensing or making printed copies of it for sale or display. Some workers, such as crime scene photographers, estate agents, journalists and scientists, make photographs as part of other work. Photographers who produce moving rather than still pictures are often called cinematographers, videographers or camera operators, depending on the commercial context.

The term professional may also imply preparation, for example, by academic study or apprenticeship by the photographer in pursuit of photographic skills. A hallmark of a professional is often that they invest in continuing education through associations. While there is no compulsory registration requirement for professional photographer status, operating a business requires having a business license in most cities and counties. Similarly, having commercial insurance is required by most venues if photographing a wedding or a public event. Photographers who operate a legitimate business can provide these items.

Photographers can be categorized based on the subjects they photograph.

Some photographers explore subjects typical of paintings such as landscape, still life, and portraiture. Other photographers specialize in subjects unique to photography, including sports photography, street photography, documentary photography, fashion photography, wedding photography, war photography, photojournalism, aviation photography and commercial photography. The type of work commissioned will have pricing associated with the image's usage.

The exclusive right of photographers to copy and use their products is protected by copyright. Countless industries purchase photographs for use in publications and on products. The photographs seen on magazine covers, in television advertising, on greeting cards or calendars, on websites, or on products and packages, have generally been purchased for this use, either directly from the photographer or through an agency that represents the photographer. A photographer uses a contract to sell the "license" or use of their photograph with exact controls regarding how often the photograph will be used, in what territory it will be used (for example U.S. or U.K. or other), and exactly for which products. This is usually referred to as usage fee and is used to distinguish from production fees (payment for the actual creation of a photograph or photographs). An additional contract and royalty would apply for each additional use of the photograph.

The contract may be for only one year, or other duration. The photographer usually charges a royalty as well as a one-time fee, depending on the terms of the contract. The contract may be for non-exclusive use of the photograph (meaning the photographer can sell the same photograph for more than one use during the same year) or for exclusive use of the photograph (i.e. only that company may use the photograph during the term). The contract can also stipulate that the photographer is entitled to audit the company for determination of royalty payments. Royalties vary depending on the industry buying the photograph and the use, for example, royalties for a photograph used on a poster or in television advertising may be higher than for use on a limited run of brochures. A royalty is also often based on the size at which the photo will be used in a magazine or book, and cover photos usually command higher fees than photos used elsewhere in a book or magazine.

Photos taken by a photographer while working on assignment are often work for hire belonging to the company or publication unless stipulated otherwise by contract. Professional portrait and wedding photographers often stipulate by contract that they retain the copyright of their photos, so that only they can sell further prints of the photographs to the consumer, rather than the customer reproducing the photos by other means. If the customer wishes to be able to reproduce the photos themselves, they may discuss an alternative contract with the photographer in advance before the pictures are taken, in which a larger upfront fee may be paid in exchange for reprint rights passing to the customer.

There are major companies who have maintained catalogues of stock photography and images for decades, such as Getty Images and others. Since the turn of the 21st century many online stock photography catalogues have appeared that invite photographers to sell their photos online easily and quickly, but often for very little money, without a royalty, and without control over the use of the photo, the market it will be used in, the products it will be used on, time duration, etc. These online stock photography catalogues have drastically changed the landscape of the industry, presenting both opportunities and challenges for photographers seeking to earn a living through their craft.

Commercial photographers may also promote their work to advertising and editorial art buyers via printed and online marketing vehicles.

Many people upload their photographs to social networking websites and other websites, in order to share them with a particular group or with the general public.[4] Those interested in legal precision may explicitly release them to the public domain or under a free content license. Some sites, including Wikimedia Commons, are punctilious about licenses and only accept pictures with clear information about permitted use.

Leah did an amazing job taking my daughter’s Senior pictures. We had some ideas we shared with her prior to the session and Leah had locations picked for us and suggestions of where to buy items for our pictures. She was quick and efficient with our time. I would highly recommend L. Severson Portraits.

Leah has been photographing my family for 15.years. She has perfectly captured my daughters’ personalities in every photo through the years! Whether it is family photos or high school senior photos, Leah has been professional, easy to work with and makes every session fun! I can’t thank Leah enough for every moment in time that she has captured of my family so beautifully!

Most photographers take between four and six weeks to share their photos, though some may turn them around as quickly as two weeks and others take two months or so. Before hiring your photographer, be sure to read their contract, which should specify a range of how long you should expect to wait for your photos.

A photographer is a professional who uses their technical expertise, creativity, and composition skills to record and produce still images that tell a story or document an event. Mar 10, 2024

Photographers create visual images for an exceptional range of creative, technical and documentary purposes. As a professional photographer, you'll usually work to a brief set by the client or employer.